Cutting through the noise on old‑growth forests

Wednesday, June 16, 2021

Let’s clarify what’s happening on old-growth vs what the government says is happening

Have you landed a meeting with your MLA? Waiting to hear back about one? Exchanging emails with your representative, or a member of their staff? Or are you just looking to make sense of the BC government’s new approach on old-growth, what’s changed, and what hasn’t?

You’re in the right place.

Whether you’re planning to ramp up pressure on Premier John Horgan or just looking to learn more, this resource is for you.

Things are changing. Years of hard work from tens of thousands of people have forced the BC government to blink and shift away from its stubborn insistence that all is well in the woods.

On November 2, 2021, the province announced for the first time ever, it would be aligning its forest inventory with science and it intends to defer logging for two years in 2.6 million hectares of the most threatened old-growth forests, with the goal of using that reprieve to work with First Nations to protect these forests forever. It’s late in the game to admit the problem and set goals to do better, but this is a welcome first step.

There was a lot of detail in the announcement, and a few days after it was made we held a webinar to do our best to break it down for people.

The long battle to see the forest for the trees

For years, the province pointed to a convenient culprit for the conflict around old-growth forests in BC: there was no agreement on how much was left and what level of threat it was under. This was a frustrating stance, as it avoided the fact that a lot of this misunderstanding resulted from the government exaggerating the amount of remaining and protected old-growth. It side-stepped the simple truth that most people want old-growth forests protected.

In the absence of an up-to-date scientific inventory, classifying old-growth was left to independent scientists to assess certain characteristics — age, tree height, etc and provide estimates around remaining percentages.

For example, mapping the old-growth forests capable of growing the tallest trees, experts at Veridian Ecological Consulting calculate just 3 per cent of that type of old-growth remains in BC. On the other side, logging corporations and the BC government lumped all old forests, regardless of characteristics, to over-inflate the remaining old-growth.

Finally, in the summer of 2021, as the RCMP arrested hundreds of people on logging roads around Fairy Creek, the Horgan government struck a committee of foresters and scientists to classify and map old-growth. It highlighted the ecologically at-risk old-growth forest the Old-Growth Strategic Review (OGSR) panel had recommended the government set aside a year earlier.

The work done by these experts is what now informs the province’s forest inventory and its approach on old-growth, and that’s a good thing.

How much old-growth is left in BC?

Let’s break it down.

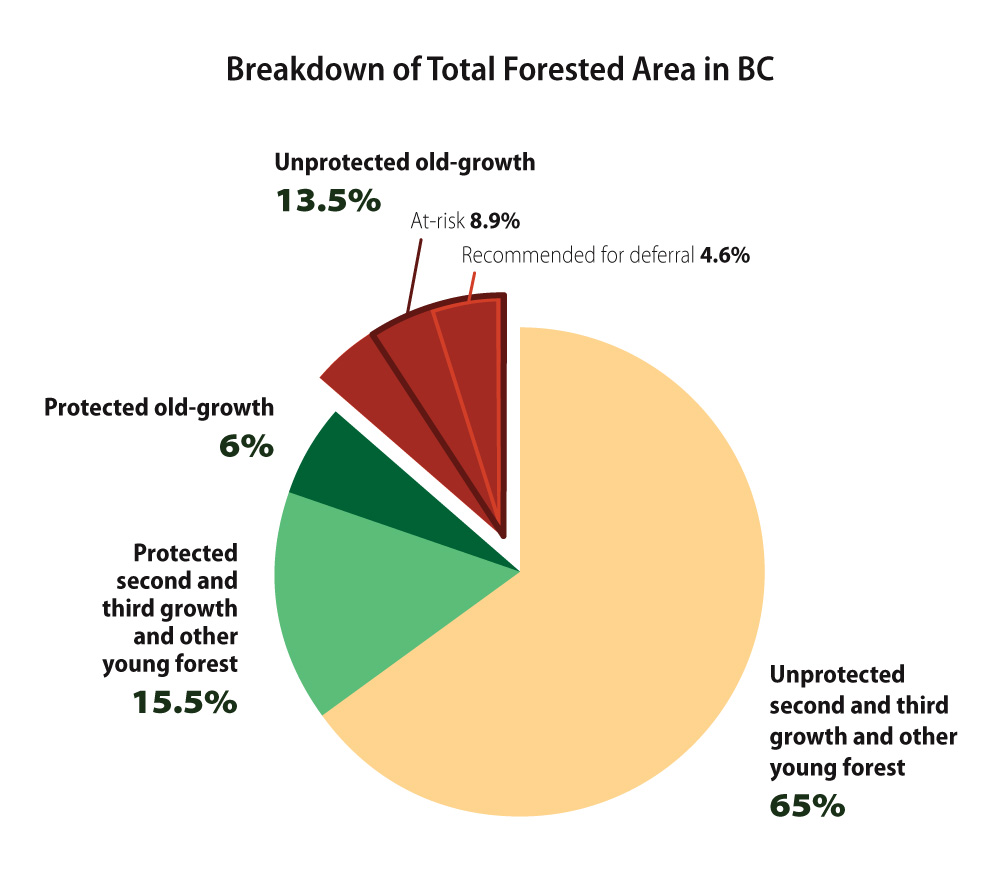

Over BC’s total claimed land area of 94 million hectares, about 56.2 million hectares — an area larger than France — is covered in forest. Of that, 11.1 million hectares meet the definition of old-growth, which is 140 years old in the interior and 250 years old on the coast (there are a few problems with this definition, more on that later).

Of that 11 million, 7.6 million hectares are unprotected, and of that, 5 million hectares are considered ecologically at-risk.

On November 2, the government announced it intends to defer just over half of that — 2.6 million hectares.

You can see these numbers on a table on the government’s website, and to see them as percentages of the total forest area in BC, check out our pie chart below:

If maps are more your speed, check out what this looks like across BC on our new ArcGIS web map.

What’s improved, what hasn’t

It shouldn’t be the case that finally aligning inventory numbers with a scientific approach marks a positive step forward in 2021, but that’s how bad things are in BC.

The adoption of the new approach is a good first step. Still, it won’t amount to meaningful change for old-growth forests without follow-through to set old-growth forests aside.

First thing’s first, let’s talk about where the new approach falls short.

The provincial definition of old-growth as forest that contains trees an average of 140 years old in the interior and 250 years old on the coast is generally useful, but it’s flawed in some aspects.

This definition is based on average tree age, which means certain types of forests aren’t considered old-growth even though they’ve never been logged. Some old forests, especially on steeper slopes, feature exceptionally old trees surrounded by lots of younger trees. If a stand of forest contains two 1,000-year-old trees and a hundred 200-year-old-trees, it’s not technically old-growth, as the average is 215 years.

This is an obvious problem, as the vast majority of BC has been impacted by industrial activity. We should be looking to protect all of the landscapes that haven’t been. The BC government must clearly state that the old-growth it intends to defer is the starting point, not the end game, when it comes to setting areas aside to provide for other values.

When it comes to threatened at-risk old-growth, the province has stated it only intends to defer logging in 2.6 of the total 5 million hectares of at-risk old-growth in BC. This means almost half of the at-risk old-growth will remain open to logging. The Old-Growth Strategic Review panel recommended the immediate deferral of at-risk old-growth forests. That’s what is required to prevent the irreversible loss of biodiversity — that’s what’s at stake as the government delays.

Government isn’t putting its money where its mouth is

The key piece missing from the government’s new approach is money. Substantial funding is required to make deferrals and eventual old-growth protection a reality. The BC NDP continues to withhold this.

Horgan and forest minister Katrine Conroy have stressed the importance of not protecting old-growth without agreement from First Nations. This is, of course, an important stance, as every tree in BC grows in the territory of a First Nation. Still, this position must be taken with the recognition that many Indigenous communities are involved in the logging industry. So there are economic barriers to setting old-growth forests aside for some First Nations. As the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) and others have pointed out, old-growth deferrals must be accompanied by fulsome resources to make them possible for all communities.

This must include immediate compensation to offset any lost revenue due to the deferrals, funding to support First Nations in assessing the impacts of permanent protection and long-term funding to invest in economic development other than old-growth logging.

This is an extremely frustrating part of the BC NDP’s approach. This government has essentially abdicated much of its responsibility to protect old-growth to First Nations without providing the support needed to move forward on deferrals.

Finally, this situation exposes the infuriating double-standard the province is operating under. It requires First Nations’ consent to protect old-growth but not to cut it down. It needs to end.

The BCTS anomaly

Overall, the provincial government announced the 2.6 million hectare deferral target without implementation. However, the one exception is the operating areas of BC Timber Sales (BCTS).

BCTS is a provincial government agency responsible for about one-fifth of all logging in the province, including some of the most controversial old-growth logging.

Around 560,000 hectares of the 2.6 million hectare deferral target is within BCTS areas. The government has indicated that any planned logging and road building within this area will go ahead, but new work will not, effective immediately.

That the deferrals are immediate within BCTS, but not the other 80 per cent of forests, suggests the delay is less about Indigenous rights and more about the government’s aversion to stepping on the toes of logging companies.

How to respond to the false and misleading claims on old-growth

As with a lot of environmental issues, there is a large gap between what the government is doing and what the government says it’s doing.

For years, the BC government has painted a rosy picture of what’s happening in the woods and what measures it’s taking to manage forests. While the adoption of science-based inventories for old-growth forests is a step in the right direction, there is still a lot of oversimplification on the part of both the province and individual MLAs. Claims are made to justify the glacial pace of the government’s talk-and-log approach.

We’ll break down a few of those claims below.

Claim #1: “BC is taking action to defer 2.6 million hectares of old-growth forests.”

As we explained above, on November 2, 2021, the government stated its intention to defer logging in 2.6 million hectares of at-risk old-growth. Intentions don’t stop chainsaws.

Outside of BCTS areas, which again are about one-fifth of all forests, none of the deferrals were implemented. The government asked First Nations to indicate where they stand on the proposed areas within a ridiculous 30-day timeline. Meanwhile, clear-cut logging can continue as usual within these irreplaceable ancient forests.

Mapping analysis done by the Wilderness Committee revealed that more than 50,000 hectares — four times the size of the City of Vancouver — has been approved for logging within the 2.6 million hectares targeted for deferral. This includes several thousand hectares of cutblocks that were applied for in the month after the government announced its intentions with the deferrals.

What’s more, even if most of this 2.6 million hectare target is eventually deferred, that still leaves 5 million hectares of old-growth forests. Almost half of that’s classified as at-risk, open to logging. The 2.6 million hectares must be deferred immediately. This must be a first step to be followed by further protection of old-growth forests.

Claim #2: “BC deferred logging in an additional 200,000 hectares of old-growth in September 2020.”

The BC government holds this up as a major action on old-growth to date. In response to the OGSR report, the Horgan government announced two-year logging deferrals across nine areas in BC. It called it “353,000 hectares” without clarifying the details, which are:

- more than 150,000 of these hectares are either non-forest (rocky outcrops, swamps, cliffs, etc.) or second-growth, which is still open to harvesting

- the area that’s old-growth area only totals 196,000 hectares, and of that

- Tens of thousands of hectares were already set aside or protected

- The vast majority is higher-elevation, less productive forests with smaller trees

- Very little of these deferrals contained old-growth forests that can be classified as at-risk

Claim #3: “BC will not make decisions about forestry policy without meaningful consultation with First Nations and we can’t set any forest aside without respecting the title holders.”

This is an excellent standard, but it’s currently double-standard, as logging and other forms of resource extraction do not currently require agreement from First Nations. Partnership deals and revenue sharing agreements are offered, but the choice Indigenous communities are given isn’t “yes or no” to logging, it's “yes or no” to receiving a (very small) share of the benefits — logging is happening either way. This isn't a fair choice after more than 150 years of colonization.

Saanich North and the Islands MLA and Tsartlip First Nation member Adam Olsen breaks this dynamic down.

Many First Nations do benefit from logging, and so there are economic barriers to accepting deferrals and exploring permanent protection. Without providing funding to offset any lost revenues resulting from deferrals and support nations in moving towards permanent protection and developing economic alternatives, the BC government can’t honestly claim it’s trying to protect old-growth.

The UBCIC has criticized the government’s approach and called for an immediate deferral of logging in threatened old-growth with immediate compensation for First Nations.

The BC government is doubling down on the status quo. It then points to Indigenous rights as the reason it isn't protecting old-growth. What it should be doing instead is fulsome, province-wide engagement with First Nations around economic alternatives. The government should be removing the barriers to setting old-growth aside by replacing any lost revenue.

The OGSR panel recommended the BC government immediately defer logging in at-risk old-growth forests to prevent irreversible biodiversity loss. This loss is what's at stake if the government continues to drag its feet.

The BC government must immediately defer logging in at-risk old-growth forests, compensate First Nations for any lost revenue in the short term and provide funding for long-term planning with nations on permanent solutions.

Claim #4: “Moving too fast on old-growth protection could jeopardize jobs and impact communities.”

Look! It's another line from the ‘Greatest Hits’ of reasons why we can’t move quickly to prevent the loss of old-growth. This argument has been trotted out once again in response to the government’s announcement that it might defer some old-growth logging.

The simple truth is that the forest industry in BC is in trouble, but it’s not because of conservation.

Decades of unsustainable logging, compounded by the mechanization of the industry, investment by logging companies in other jurisdictions and climate change-fueled wildfires have resulted in tens of thousands of jobs lost over the last few decades — a time span that hasn’t included a dramatic increase in conservation.

Here’s why the scapegoating of environmentalism for the problems in the forest industry needs to end.

Mills have closed, and jobs have been lost for the same reason caribou are on the brink of extinction and thousand-year-old trees are still falling. The logging companies have cut too much, too fast, for too long. Over a century of unsustainable management has caught up to us.

We need a paradigm shift to ensure the survival of irreplaceable old-growth, yes, but also to ensure sustainable forestry is an option in the future. Forest communities can thrive.

Claim #5: “There is lots of old-growth left.”

This is a myth, and it's time to lay it to rest forever. When we talk about old-growth, we’re talking about the most special forests that grow here, not just any forest of a certain age class. Government and industry have long lumped high-elevation or shoreline bog forests with smaller, stunted trees in with the iconic old-growth that we all identify with the term. The new science-based inventory of what’s left done by the Technical Advisory Panel is a huge improvement. It lays out just how scarce the most threatened old-growth forests are.

As the government’s inventory table and the pie chart further up in this article show, the vast majority of forested area in BC is unprotected forest that’s not old-growth. A sustainable forest industry can and should take place there.

The myth that there’s lots of old-growth should now be recognized as such.

Claim #6: “The previous government refused to act”

Frankly, a remarkable point for this government to make, after dragging its heels on implementing the OGSR recommendations for 18 months and counting. The OGSR panel did not recommend the deferral of at-risk old-growth for fun. They did it to prevent irreversible loss of biodiversity. That’s what’s at stake as the BC NDP refuses to actually change things on the ground.

This also comes after the BC NDP broke its promise to implement endangered species legislation, which would ensure the protection of old-growth forests in many important habitats. This government has been in power for more than four years. It’s promised to save old-growth forests, and they’re still being cut down.

This failure to act is entirely on them.

A deciding moment for the fate of old-growth forest

Decades of hard-fought activism has forced the BC government to admit that serious change is needed. But the status quo is deeply entrenched, and those in power won’t let go of it easily.

This is a crucial time to ramp up our efforts to protect the last old-growth forests.

In the weeks and months ahead, we’ll be rolling out more updates and ways to get involved – stay in the loop on our website, Facebook and Twitter feed, and for updates on this campaign, subscribe to our e-alert list.

In the meantime, continue to raise your voice and put pressure on the provincial government. It’s what has helped get us this far, and it’s what will help win protection for irreplaceable ancient forests.