The Seymour Saga ‑ Shared Vision

Monday, December 14, 1998

December 15th, 1998

Joe Foy

Have you ever visited the Seymour Valley? The upper portion of the valley (closed to public access) is one of the main sources of drinking water for the people of Greater Vancouver, and the lower portion of the valley is an extremely popular recreation area seeing 250,000 visits per year. The Seymour is also home to some of the tallest trees in Canada and site of one of the longest running conservation vs. logging battles in B.C. history.

The Seymour River rises in the wilds of the Coast Mountains, carves its way through a spectacular canyon, then winds its way through the outskirts of the city of North Vancouver before entering Burrard Inlet, near the Second Narrows Bridge.

The story of the Seymour River in the 20th century is a fascinating saga of how one person really can make a difference. It's also a cautionary tale of how we humans may be mere mortals, but rivers are eternal and need defenders in each new generation.

In 1906, alarmed at how fast lower Seymour lands were being bought up by logging companies, the provincial government of the day reserved portions of the valley for the future water supply needs of the new and rapidly growing city of Vancouver. By 1908 Seymour River water was flowing through Vancouver taps. Sadly, logging continued to spread in the unprotected sections of the watershed. By the early 1920s logging in the Seymour was so aggressive that it was causing concerns for public health. In 1924 Ernest Cleveland, the provincial water comptroller kicked off the conservation vs. logging fight by saying to the Engineering Institute, "The watersheds on the north shore are a heritage for this whole area... To allow anybody to get entrenched on Seymour Creek with logging and shingling operations would be almost criminal".

In the summer of 1925 a forest fire, sparked in logging slash in the neighbouring Capilano watershed, lasted for several weeks and incinerated 1,400 hectares of timber. The fire caused great public protest leading to the creation of the Greater Vancouver Water District (GVWD). In 1926 Cleveland became the GVWD's first commissioner, a position he held until his death in 1952. Cleveland began his tenure by saying "They will log that watershed over my dead body," a promise he steadfastly kept for the rest of his life. He ordered private lands held by timber companies to be purchased and he shut down logging in the north shore watersheds, including the Seymour.

Ernest Cleveland successfully protected the remaining ancient forests of the Seymour River for 26 years. Further east in the community of Surrey which was only a scattering of small villages, the last stand of oldgrowth forest at Green Timbers was cut in 1929. All up the Fraser Valley the once great valley-bottom rainforests were almost completely logged out. Yet somehow Ernest had successfully "locked up" magnificent groves of 30-storey-tall giants just across the inlet from the metropolis of Vancouver. What a tremendous accomplishment and gift to future generations.

One year after Ernest had passed away, two things began to happen. The GVWD hired forestry consultant CD Schultz Co. to provide an inventory of the Seymour and two other watersheds (Capilano and Coquitlam). The Schultz company recommended that sustained yield logging occur in all three of the watersheds. The second, seemingly unrelated happening was that Mr. and Mrs. Kelman of Vancouver took their young son Ralph on the first of many picnic trips to the tall timbers of the lower Seymour River.

From 1958 until 1960 the current dam on the Seymour river was constructed. Former employees of Schultz Co. clearcut the valley-bottom forests upstream from the dam site in preparation for the reservoir. The GVWD's forester, also a former Schultz Co. employee, recommended that the remainder of the forests in the lower Seymour below the dam (noncatchment lands) and the upper Seymour above the dam (catchment lands) be logged to combat the spread of balsam woolly aphids -- an insect naturally found in the rainforest that feeds on amabilis fir. It was like recommending that your home be bulldozed to combat house flies. Aggressive clearcut logging launched into high gear. Boy, did the people of Vancouver ever need Ernest -- but Ernest was gone and no one had taken his place as guardian of Vancouver's rainforest.

Between 1961 and 1992 the GVWD built an extensive network of logging roads and clearcut the giant trees on the same private lands which Ernest Cleveland had purchased from the timber companies back in the 1920s for conservation. Eventually the majority of the Seymour's valley-bottom oldgrowth was clearcut and Ernest's dream of a forest preserved for the public good seemed to be forgotten.

Then, in 1990 a lone hiker thrashing through the dense rainforest undergrowth signalled a reawakening of the spirit of Ernest Cleveland. Little Ralph Kelman had grown up and was

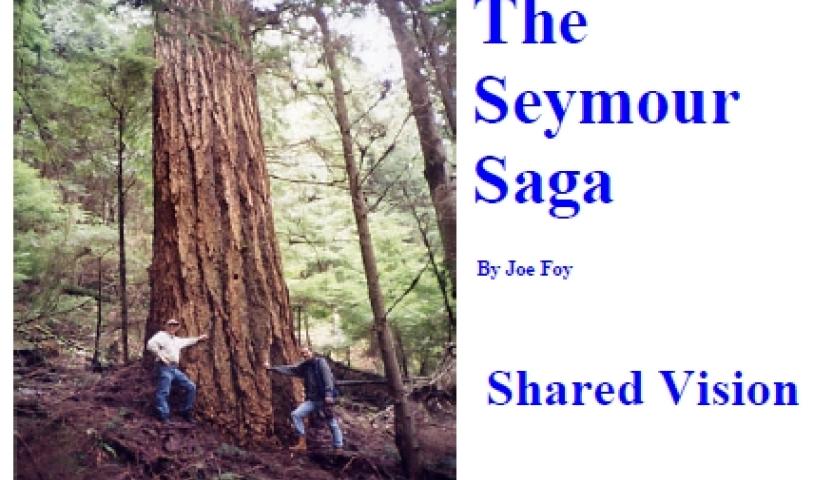

hunting for remnants of Cleveland's dream in the Seymour -- and he found them. For the past eight years Kelman has been laboriously locating, measuring, naming and mapping the surviving big trees of the lower Seymour Valley. About a third of the lower Seymour's original oldgrowth forest still remains. He has found dozens of record trees -- including the "Temple Giant", a Douglas fir 300 feet tall and 11.5 feet in diameter, the "Curley Chittenden Giant" another huge Douglas fir over 9 feet in diameter and the "Tolkien Giant", a massive western redcedar. These are amongst the biggest trees in Canada, yet they are right next to the two million people of Greater Vancouver.

Incredibly, Kelman has done all this work on a shoestring budget, using the bus system to get to the valley, packing a beat-up old camera to collect photos, hand drawing the maps and using a rusty bike with only two working gears (slow and slower) that he purchased for $10.

Kelman's giants have galvanized Vancouver area conservationists, including Western Canada Wilderness Committee (WCWC), into a force to be reckoned with in the Seymour Valley. In 1992 conservationists garnered a temporary halt to logging in the Seymour, which holds to this day. But, as we have seen in the past, logging could start up again as soon as public vigilance subsides.

WCWC is calling for a permanent ban on logging in the entire Seymour Valley (and the Capilano and Coquitlam) as well as for the designation of the lower Seymour Valley catchment lands as the "Seymour Ancient Groves Park". Currently the lower valley is designated as the "Seymour Valley Demonstration Forest" where logging can be "demonstrated" to the general public.

WCWC has produced a four page information newspaper about the giants of the lower Seymour River and what you can do to help make the Seymour Ancient Groves Park a reality. WCWC has also produced a hiking map so that you and your family and friends can visit the giants for yourself. Take your kids. The Seymour giants are going to need future Ernest Clevelands and Ralph Kelmans to protect them over the coming years, decades and centuries.

For copies of WCWC's Seymour newspaper and hiking map visit WCWC's store at 227 Abbott Street in Gastown or phone 683-8220.