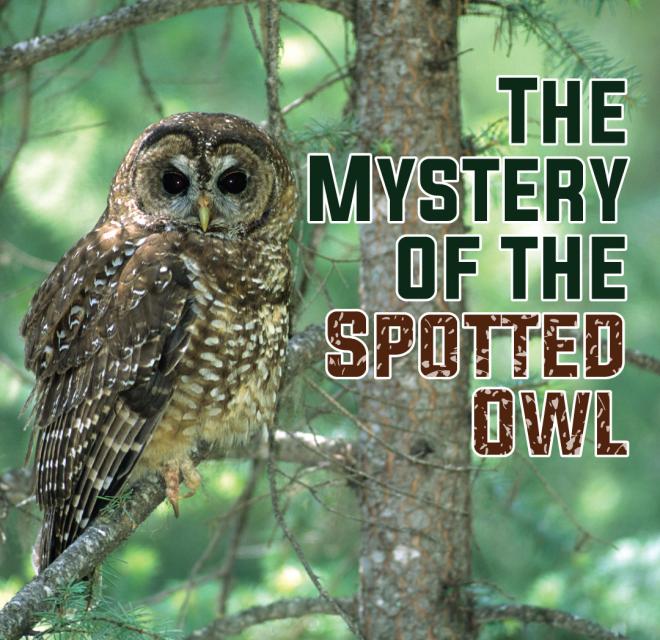

The Mystery of the Spotted Owl

A WHODUNIT STORY: THE FINAL CHAPTER

In my work to conserve wild nature spanning more than 30 years, I’ve witnessed the population of endangered spotted owls in Canada dwindle to almost nothing in southwest mainland BC, the only place in the country they’re found. Before the start of industrial logging, there were once about a thousand spotted owls living in the old-growth forests of the Lower Mainland. Today, after more than a century of out-of-control clearcutting, only one wild-born spotted owl still survives in its forest habitat.

The smoking gun in the sad case of the spotted owl’s decline is poorly regulated industrial logging.

Who’s been killing off the spotted owl in Canada? The story of the people behind the demise of at-risk spotted owls is every bit as dark and murky as a classic murder mystery tale.

Tell BC: stop logging spotted owl habitat, permanently

Who are the usual suspects?

The logging companies and their owners would be a reasonable guess. After all, these are the people who profited from the felling of the magnificent old-growth forests that once blanketed the Lower Mainland. But there’s a problem with only blaming industry. Pretty much all of the logging has been and continues to be done under permit from the BC government. At the same time, since 2002, the government of Canada has had a Species at Risk Act (SARA) that applies to species like the spotted owl. Both governments not only have an obligation to protect the owls but also to take into account the wishes of the Indigenous Peoples whose unceded lands are being logged. Properly managed logging should not endanger species like the spotted owl.

Both governments have failed miserably to support Indigenous Peoples’ aspirations to keep their lands and waters healthy.

Who are the prime suspects?

The elected leaders of the governments of BC and Canada are the people most responsible. Premier David Eby and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and all of their predecessors are guilty of failing to ensure logging is properly regulated. Both governments have cooperated on many significant programs to conserve and protect some spotted owl habitat. They have even put in place the only spotted owl breeding facility in the world, with two offspring being successfully released to the wild for the first time last year. However, successive provincial governments have been slow to stop granting permits to logging companies for the clear cutting of old-growth forests. And successive federal governments have done little more than hand wringing and belly aching instead of applying SARA to stop BC from permitting logging of the spotted owl’s dwindling habitat until the minister recommended an emergency order this year to stop some logging of their habitat. Both governments have failed miserably to support Indigenous Peoples’ aspirations to keep their lands and waters healthy.

Now that you know the whodunit of the spotted owl story, read on to learn what we can and must do together to save this beautiful wild creature from disappearing from Canada and why it is so important to do so.

Help write the final chapter that brings this endangered species back from the brink.

BACKROOM DEALS SELL OUT OWLS

Last December in Montreal, governments from around the world came together for almost two weeks at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference to agree on new goals to guide global action through 2030 to halt and reverse nature loss and species extinction.

Before this, Trudeau had made international commitments to protect 30 per cent of lands and waters in Canada — in partnership with Indigenous Nations — by 2030. In December, Eby made a similar promise for BC.

Both elected leaders correctly described the urgent problem of species loss and habitat depletion and supported a good policy to begin to turn around species endangerment — protect 30 per cent of all lands and waters by 2030, working with Indigenous Nations.

The words said, and promises made at the Montreal meeting by BC and Canada were uplifting and inspirational. But the secret backroom deals being cut on spotted owl habitat at the very same time were downright reprehensible.

For many years the federal government had been pushing BC to stabilize and recover the highly endangered spotted owl population. For several decades the two governments argued while spotted owl numbers continued to decline in the face of logging in the owl’s habitat under permits handed out by BC.

In 2019 the federal government finally began to craft a proper spotted owl recovery plan, as required by SARA, and produced a draft map of critical habitat in October 2021. Much of the remaining low-elevation old-growth forest in the Lower Mainland, and even some older second-growth forest, were mapped out in detail. Effort had been taken to provide for forested wildlife corridors between habitat areas.

But then, in January 2023, Canada released the draft spotted owl recovery plan for public comment. In a shocking plot twist, a revised critical habitat map for the spotted owl was revealed. Over 100,000 hectares of critical habitat — an area of forest similar in size to Garibaldi Provincial Park — was stripped of critical habitat status and re-designated as potential future critical habitat.

However, there is no potential future of the spotted owl if all of the owl’s habitat isn’t identified for protection. This is why urgent efforts are needed now to get the federal government back on track and protect all of the spotted owl’s forest habitat immediately if this species is to survive and recover to healthy numbers.

FIGHT OVER SPOTTED OWLS MEANS SAVING OLD-GROWTH FORESTS

The spotted owl’s range is limited to the southwest corner of mainland BC, extending from the village of Lillooet south to the border with the US, and from EC Manning Provincial Park west to the shore of Howe Sound. Within the range of the spotted owl are the territories of about 50 Indigenous communities representing several Salish languages, including Halq’eméylem, N?e?kepmxcín, Sƛ’aƛ’imxǝc, SEN?O?EN and Sḵwxwú7mesh.

Ever since industrial logging first started up in the Burrard Inlet in the 1860s, any attempts to protect old-growth forests coveted by the logging industry turned into a battle. Which logging interests usually won. That’s why communities like Burnaby, New Westminster, Surrey or Langley have pretty much no remaining old-growth forests — just some big stumps scattered around here and there.

But some forest fights did end up protecting old-growth. In 1926, then-Vancouver water commissioner Ernest Cleveland declared logging in the watersheds that supply Vancouver with drinking water “would continue only over my dead body.” Logging ceased under Cleveland’s stewardship but then started up again in the 60s after he passed away. In the 90s, activists took up his example and successfully got the logging stopped for good. Today the Coquitlam watershed still contains some of the oldest and tallest trees in Canada. It is renowned for producing some of the finest drinking water, due to the old-growth forest found there.

Throughout the 80s and 90s, Lytton First Nation, led by Chief Ruby Dunstan, was unwavering in their demand that the Stein River Valley be protected from the logging industry. They joined with their Indigenous neighbours at Mount Currie to produce a declaration pledging to protect the valley for all people. Today thanks to the leadership of these Nations, the Stein Valley is protected from logging and still contains beautiful old-growth forests as the Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux Heritage Park.

Despite these and other hard-fought wins, too much old-growth forest has been logged. This is evidenced by the terrible consequences suffered by wildlife and the First Nations and communities that depend on them. That’s why it’s absolutely critical we win the fight to see all remaining spotted owl forest habitat properly mapped and designated as critical habitat and then protected as part of the spotted owl recovery plan. This will help ensure a stable future for the owl — but also for the other wildlife and people that call this region home.

WE MUST RESPECT FIRST PEOPLES’ RIGHTS TO PROTECT TRADITIONAL TERRITORIES

By Chief James Hobart, Spô’zêm Nation

For well over a century, the First Peoples have witnessed blatant disrespect and exploitation of our Nations and Traditional Territories’ resources. In BC, the provincial government’s messaging constantly and wrongly suggests they are following ‘sustainable’ forestry practices — portraying a picture that reforestation and management will heal the land after logging.

However, in reality, and actual practice, the province’s plans require things to fall completely and predictably into place. When they don’t. Forest companies shrug off their management responsibilities for increased profits. Government-driven reforestation plans fail to cope with the negative impacts of invasive species, bug-killing pesticides, forest fires, atmospheric rivers, shrunken wetlands and over-logging.

We’re now bearing witness to the negative ramifications of this gross misrepresentation by the BC government.

It’s clear now to us, as it should be to everyone, the developers of provincial forestry plans grossly fail to take into consideration the many indicators available as they forge ahead despite ample evidence their plans have gone miserably wrong.

We, the First Peoples, are and have been caretakers of these lands since time immemorial — observing, protecting, preserving and respecting the lands on which we all rely for life itself. There are natural environmental indicators of the state of the lands and waters that are measurable through honest mapping and research. These indicators are larger than life for Nations who bear witness to the loss of innumerable parts of the ecosystem each day — some of which are damaged or depleted beyond repair or recovery.

Natural indicators include:

- The early rush of water into waterways from snow melt, which affects every salmon run in every salmon stream

- The endangered grizzlies, which require wooded wildlife corridors to live and hunt now face extinction in many traditional territories

- The northern spotted owl, which requires an even-more unique corridor than the grizzly, as it only lives in old-growth forests. Currently, only one wild female owl is known to remain, three if we include the two recently released captive-bred owls.

Grizzlies and spotted owls are known as umbrella species as they represent countless other species that sustain our ecosystems. It’s clear now to us, as it should be to everyone, the developers of provincial forestry plans grossly fail to take into consideration the many indicators available as they forge ahead despite ample evidence their plans have gone miserably wrong.

When they developed these so-called sustainable forestry plans decades ago, the momentum of industry and desire for market growth made it impossible for them to properly review data and environmental indicators, nor take action to mitigate the damage of this flawed process. Now we’re seeing the outcomes. Behind the scenes, the BC government says they need replanted forests to grow for another 20 years for trees to reach a size where they can be logged at a profit again. Why is the only way to fill that 20-year gap to log the remaining old-growth forests?

When we, as Indigenous Peoples, harvest medicines, it becomes clear that some of the most valuable plants and roots are found only in our ancient forests. BC must stop applying monetary value to something sacred and life-giving. Yet their pace quickens and the signs are consistently ignored. Only once we get past the point where trees are strictly viewed and treated as a commodity can we retain our reputations as stewards and caretakers of the land.

NOW OR NEVER MOMENT FOR SPOTTED OWLS

Things don’t look good for the spotted owl. It would be pretty hard to find a species in Canada more endangered. Even more, it serves as the “canary in the coal mine” for an entire ecosystem and the biodiversity at risk there. Not to mention a story of how government relationships with Indigenous Peoples are nowhere near reconciliation.

But believe it or not, hope still flickers in the remaining old-growth forests. And this is why protecting all of them is so important now. If enough habitat areas are protected and interconnected with forested wildlife corridors, we just might be able to keep this species from winking out and rebuild its population back to a safe self-sustaining state.

These ancient places are a spiritual and cultural touchstone for many.

Spotted owls still exist in higher numbers in the Pacific Northwest of the US. If enough quality habitat is protected here, some owls may be able to naturally relocate. In addition, the province has a one-of-a-kind captive spotted owl rearing facility in Langley and for the first time last year successfully released two captive raised male spotted owls into an area of habitat near the wild-born female.

The brightest reason for hope right now is the emergency order recommended by the federal minister to stop logging some of the habitat needed immediately and the amended federal spotted owl recovery strategy if the government agrees to identify all the critical habitat needed and protect it. If done right, it has the potential to protect enough old-growth forest habitat to allow the spotted owl to make a comeback.

That’s why it’s so shocking and infuriating that Canada seems to have caved in to BC’s demands to drastically shrink the areas designated as core critical habitat in the new 2023 draft, in the interests of logging. Correctly identified core critical habitat areas are the only ones that have a chance of legal protections under SARA.

There is much more at stake here than the spotted owl. The old-growth forests in southwest BC protect a host of species at risk and are the foundation of many of the region’s most beloved outdoor recreation destinations. These ancient places are a spiritual and cultural touchstone for many. Old-growth forests within the range of the spotted owl filter and regulate run-off water and snow melt and help to stabilize mountainsides, prevent landslides, mitigate flooding, provide clean drinking water to several million people and store climate-changing carbon.

Across Canada, more than 5,000 wild species now face some level of risk of extinction, mostly because of habitat destruction on an industrial scale. Worldwide around one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction — the highest number in human history.

Join the fight to save the spotted owls and their old-growth forest habitat. Working together, we can win back a future for owls, other wild creatures and ourselves.

WRITE PREMIER DAVID EBY AND HIS GOVERNMENT

I’LL GIVE A HOOT FOR SPOTTED OWLS!

LET'S MAKE A DIFFERENCE TOGETHER

Your gift today supports our work to protect critical spotted owl habitat and all the at-risk species who live there — through grassroots education, advocacy and action. Thank you!