British Columbia says it will no longer log in Skagit headwaters key to Puget Sound

Thursday, December 5, 2019

Amid an international dispute, British Columbia’s government announced Wednesday that it will no longer allow timber sales in the Skagit River’s headwaters.

The decision could intensify pressure over a Canadian company’s pending permit to begin exploratory mining in the area, which conservationists view as a bigger threat to the river’s ecology.

Last year, loggers built roads and clear-cut several large swaths of forest in the headwaters, which drain into the Skagit River and eventually flow through Washington state to Puget Sound.

Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan cried foul, writing to B.C. officials with “grave concern” about water quality and environmental degradation. The Skagit is a top producer of salmon for Puget Sound, it is home to endangered bull trout and its waters churn hydropower dams to bring Seattle much of its electricity.

After Durkan’s protests, B.C. officials last summer put future logging plans on hold. On Wednesday, they committed to protect the area from logging, at least.

“Timber harvesting under this license has ended. No future licenses will be awarded,” said Doug Donaldson, the minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development in British Columbia.

The decision by the B.C. government could raise negotiating stakes with Imperial Metals, a Canadian mining company that has applied to perform exploratory drilling on its mineral tenures there. Conservationists fear a potential spill of mining waste or byproduct would imperil the Skagit River ecosystem and devastate struggling salmon species.

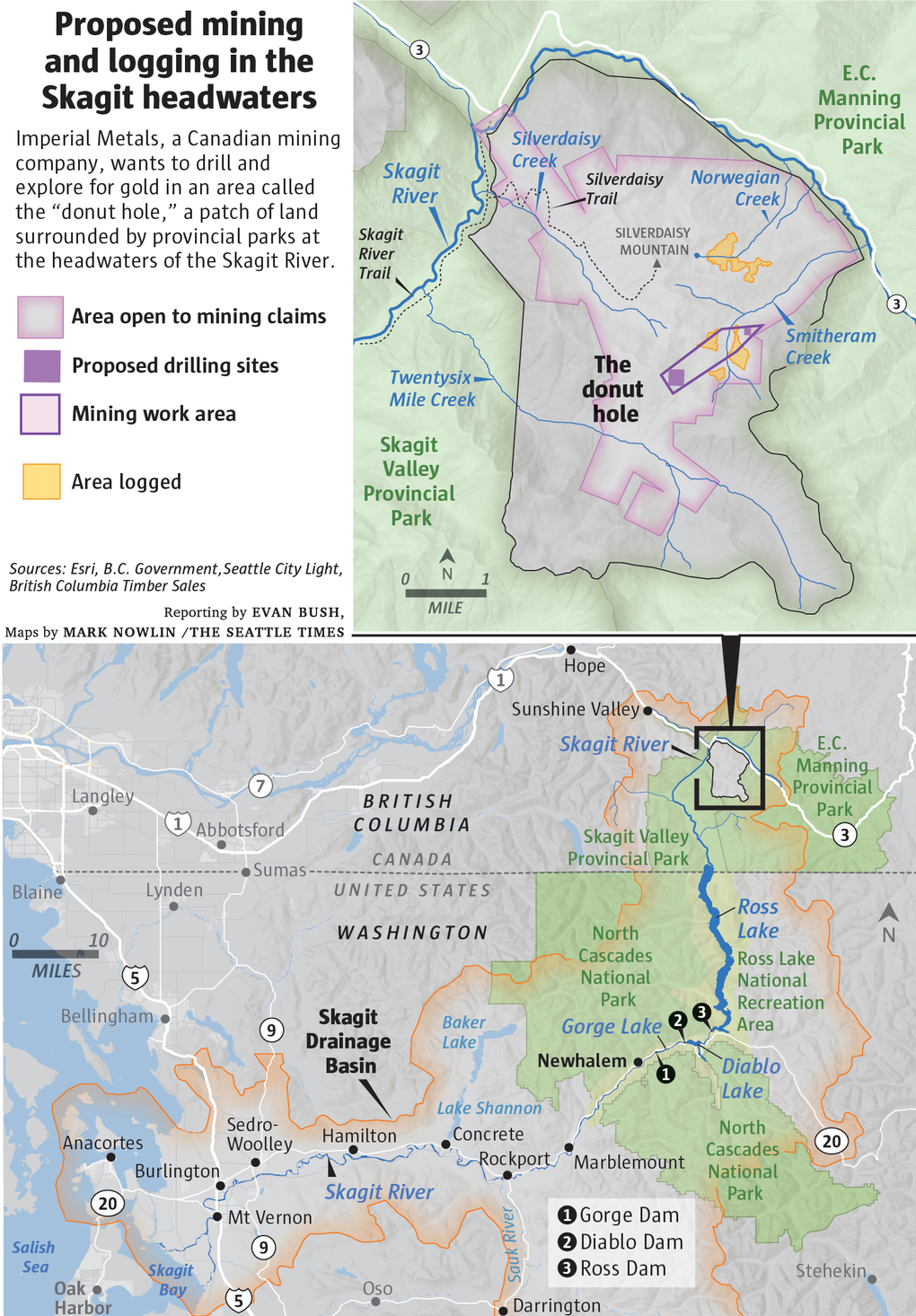

The conservationists hope to one day incorporate the unprotected land, which is often called the “donut hole,” into the Manning and Skagit provincial parks that surround it. That’s not possible until the mining rights are sorted out.

“We’ve been working to get logging banned in the area for 15 years,” said Joe Foy, the Protected Areas Campaigner for the Wilderness Committee, a Canadian environmental group. “This is a big move forward for us, but we remain nervous until the tenure is removed and the area is legislated as protected.”

Negotiations over the mining rights are ongoing, according to Thomas Curley, a Canadian appointee to the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission (SEEC), an organization created by treaty to settle prior disputes over the landscape.

Controversy over the Skagit’s headwaters kicked off in 1937 when the city of Seattle began construction of the Ross Dam on the river. The dam created a reservoir, Ross Lake, that stretches into Canada. For years, the city considered building the dam higher and expanding the reservoir farther into Canada, flooding some old-growth forestland.

Environmentalists protested. B.C. and Seattle eventually came to an agreement in 1984. Seattle agreed not to raise the dam. The Canadians promised to provide cheap hydropower to Seattle through 2065. The U.S. and Canada signed a treaty over the deal.

The agreement also created SEEC. Seattle’s mayor and B.C.’s premier each appoint four members to the commission, which works to conserve the watershed, enhance recreation and acquire timber and mineral rights.

In March, Imperial Metals applied for an exploratory mining permit in the donut hole.

The company applied to drill for as many as five years, according to project documents. Imperial Metals would extend a recently created logging road, set up trenches and build settling ponds for exploratory drilling in an area believed to have gold and copper. Metals, particularly copper, are toxic to salmon.

Imperial Metals saw an environmental disaster at its Mount Polley mine in British Columbia in 2014, when a dam there failed and allowed billions of gallons of gold- and copper-mining waste to flood into local waterways.

The B.C. government has yet to make a decision on whether to allow exploration.

Durkan said the city would continue to advocate “to fully protect the Upper Skagit Watershed from mining exploration …"

The application sparked outcry from U.S. officials, tribes and environmental groups. Nine Democratic members of Washington state’s congressional delegation called for the U.S. Department of State to intervene.

U.S. officials have pressured British Columbia over mining regulations because toxics and mining waste can flow downstream and into the U.S.

A bipartisan group of eight Western U.S. senators in June wrote to British Columbia Premier John Horgan, saying they “remain concerned about the lack of oversight of Canadian mining projects near multiple transboundary rivers.”

Read the original article published by The Seattle Times by clicking here.