Algonquin Provincial Park

End park logging

When people think of Algonquin Provincial Park, images of sparkling waters, towering pines and glimpses of moose come to mind. As the oldest provincial park in Canada, Algonquin’s natural beauty has achieved iconic status. To many, a “park” implies the highest level of nature protection and opportunities for outdoor recreation. Yet shockingly, 65 per cent of Algonquin Park lands are designated for commercial logging. Industrial activities like logging and mining are incompatible with protected parks, which is why they are banned in all other Ontario parks. It’s time to end the logging industry’s stranglehold in Algonquin Park and finally give it the protection it deserves.

Take Action

End old growth logging in Algonquin Provincial Park

Parks must protect nature

Protected areas are meant to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystems. According to Ontario’s Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act (2006), these areas should prioritize ecological integrity. Algonquin Provincial Park contains the highest concentration of self-sustaining trout lakes in the world and supports the southern range of many large mammal species in Ontario, like moose, wolves, black bears and martens. It also provides important habitat for many species of small mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, and forms the headwaters of four major rivers.

The prioritization of timber harvest in two-thirds of Algonquin Park puts these ecological values at risk, as ecosystems are managed primarily for profit. Over 6,000 kilometres of logging roads crisscross the park, dissecting ecosystems and putting wildlife in danger.

Parks for people

Protected areas are incredible places for people to develop relationships with nature, gain ecological knowledge and enjoy low-impact recreation such as canoeing, hiking and camping. Established in 1893 as a way to balance public access with logging, Algonquin Provincial Park is now situated in relatively close proximity to major population centers in Ontario. It attracts nearly a million visitors each year and often experiences overcrowding, which can also put pressure on natural areas.

Most visitors are unaware that the majority of the park’s land is managed for logging instead of public enjoyment. While more than 2,100 kilometres of canoe routes draw people to Algonquin to experience the beautiful land and water-scapes, the vast network of hidden logging roads drastically impacts both the health of the area and public access. It’s high time to end logging in Algonquin Provincial Park and prioritize people, nature and future generations.

Raising awareness

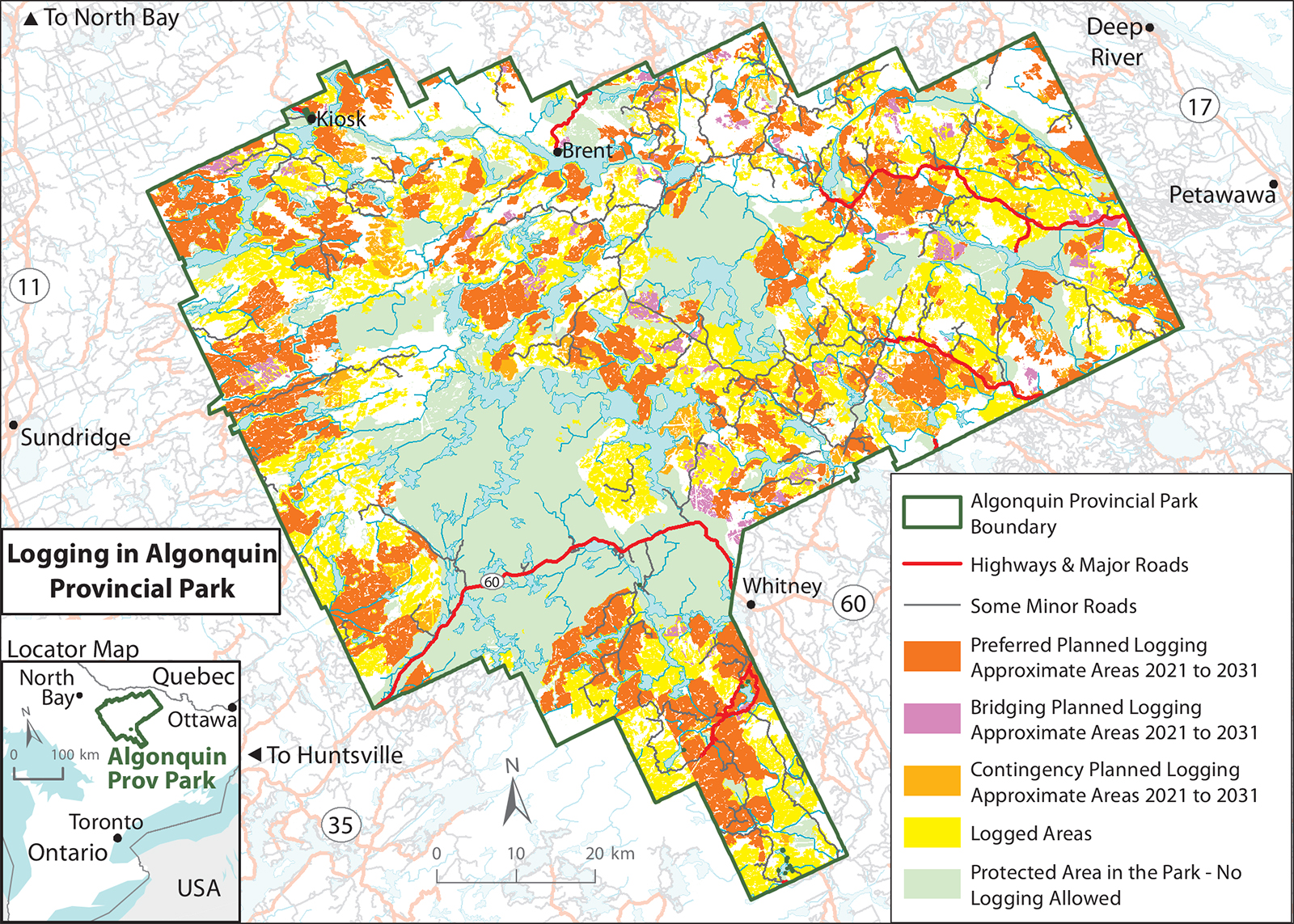

When people find out the extent of logging in Algonquin Park they are often shocked and motivated to advocate for full protection. We raise awareness through the production of maps that reveal what’s often hidden from public view. This map indicates past and future logging in yellow, red and orange as well as some of the primary logging roads.

Map of past and future proposed logging in Algonquin Provincial Park

Protecting 30x30

In a time of twin climate and biodiversity crises, the science is clear: we must protect more nature. The Canadian government has committed to protecting 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030 as a party to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Currently, only 11 per cent of Ontario is protected. The 65 per cent of Algonquin that is open to logging falls far short of these international and national standards. Protecting these areas by ending logging is a straightforward step toward meeting these essential targets.

Algonquin Park Management Plan review overdue

Ontario requires provincial park management plans to be reviewed, with public consultation, every 20 years. Algonquin Park’s plan was last revised in 1998, which means a new plan is many years overdue. Notably, the provincial government has never allowed the public to be consulted on whether logging belongs in Algonquin Park.

A comprehensive review would be an opportunity for a full environmental assessment of the impacts of logging as well as other pressures on Algonquin ecosystem diversity — as recommended by the province’s auditor general — and for public input on the future of this beloved park.

Opportunity for land-based reconciliation

While protecting nature in provincial parks is a priority for the Wilderness Committee, we also acknowledge the colonial history and ongoing injustices to Indigenous Peoples that provincial parks represent. The majority of Algonquin Park lands fall in the unceded traditional territories of multiple Algonquin Nations, who were displaced and disenfranchised by settler logging practices and by the establishment of the park borders.

The Ontario government is currently involved in negotiations for a new land claim process with the Algonquins of Ontario. Development of a new plan for Algonquin Park is a much-needed opportunity to redress these injustices and re-centre Indigenous ecological knowledge and practices in stewardship of the land.

The fight is far from over. Join us to end logging in Algonquin Provincial Park, starting with the identified unprotected old-growth stands.

Algonquin Park old-growth project

An estimated 24,000 hectares of old forest in Algonquin Park is unprotected and open to logging. Old-growth ecosystems are essential for fighting climate change through carbon sequestration and storage. They also provide valuable opportunities for research and land-based learning into the natural processes of forests free from commercial logging.

With your support, we’re working with old-growth ecologists and researchers to collect on-the-ground data on old-growth remnant forests in Algonquin Park. Since 2022, we have produced reports for key areas near Cayuga Lake, Brain Lake and Hurdman Creek. Each report is sent to the Ontario government and the Algonquin Forestry Association to help strengthen the case for protection.

On The Ground In Algonquin Old-Growth

We’re researching old-growth forest stands in Algonquin Park with Ontario ecologist Mike Henry. The 2022 scientific surveys will take place in locations that are still unprotected from logging with the goal of raising public awareness of what’s at risk as long as Algonquin remains open to industrial activity. Stay tuned for reports of the findings, and don’t forget to use our action tool below to call for full protection for Ontario’s iconic park.

What’s Up With Logging In Algonquin Park?

When most people think of Algonquin Provincial Park, images of sparkling lakes, towering trees and glimpses of moose come to mind. To many, the word “park” implies the highest level of ecological protection; however, 65 per cent of Algonquin Park is open to commercial logging. Logging is incompatible with a protected area. Check out our downloadable flyer to learn more.

Campaign Gallery

Check Out More Updates

Join Us

Don’t miss your chance to make a difference. Receive campaign updates and important actions you can take to protect wildlife, preserve wilderness and fight climate change.